When it comes to straight news reporting on the oil and gas industry, nobody outshines the New York Times.

The featured front page story in the Sunday Times (12/26) was a deep investigative piece on the Deepwater Horizon blowout. Reporters David Barstow, David Rohde and Stephanie Saul interviewed 21 survivors and pieced together the nine harrowing minutes between the mud flow at the surface of the Macondo well and the catastrophic explosion and fire.

It’s worth a read.

Nearly 400 feet long, the Horizon had formidable and redundant defenses against even the worst blowout. It was equipped to divert surging oil and gas safely away from the rig. It had devices to quickly seal off a well blowout or to break free from it. It had systems to prevent gas from exploding and sophisticated alarms that would quickly warn the crew at the slightest trace of gas. The crew itself routinely practiced responding to alarms, fires and blowouts, and it was blessed with experienced leaders who clearly cared about safety.

On paper, experts and investigators agree, the Deepwater Horizon should have weathered this blowout.

This is the story of how and why it didn’t.

In the video and slideshow sidebars, you hear several of the survivors stories in their own words, along with an animation that shows the escape route taken by two of the luckiest survivors.

This is the story from the rig workers’ viewpoint. It is told with dignity and respect for the fallen.

So what went wrong? The investigation is not complete, and “all I know is what I read in the papers”, but I’m willing to toss in a few observations.

Controlling an oil well is all about keeping well fluids (in this case, highly pressurized oil, gas and salt water) at bay. You do that by constructing multiple, redundant barriers (large pipe called well casing, cemented in place) to fluid entry and performing repeated tests of same. In case those fail, you have blowout preventers that are supposed to stop the well flow, no matter what. If those fail, (in the case of a deepwater rig) you have a system that allows the rig to detach from the well and float free.

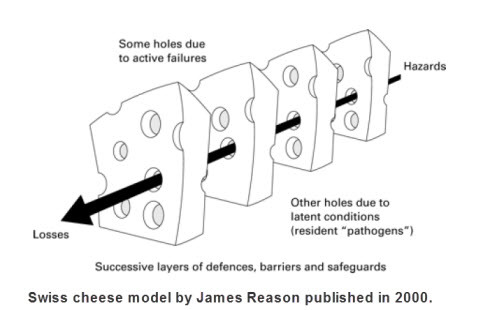

Oil and gas risk management has borrowed the “Swiss cheese model” from the work of James Reason in the health care industry to understand how risk works to keep a potential hazard from becoming an accident:

Each barrier to the hazard is represented by a slice of Swiss cheese. The holes in a slice represent imperfections in that barrier. Since each slice can (theoretically) prevent the hazard from escalating to an accident, it is only when a set of holes align that catastrophe happens.

Just for illustration, let’s say there are 8 barriers in a robust Macondo-type well.

If each has a failure rate of 10% individually, a “loss” will be experienced only if all of the failures “line up”, an event that should happen once in 10,000,000 trials.

Theoretically.

In the real world, barriers/slices can be bypsassed or eliminated (as BP did in designing the well without a liner/tieback system). More often, we make the holes bigger (more prone to fail) by skimping on maintenance (as Transocean reportedly did with BOP maintenance) or by misinterpreting casing test results (BP and Transocean).

But perhaps the biggest variable is human response. Some of the barriers require active human intervention. The Horizon was largely automated, which allowed for “multitasking”; as a result, most of the drill crew was working at other duty stations when the well blew in.

Upon reading the article, I was struck with a few “if onlys”.

- If only the crew had diverted the well overboard instead of to the gas separator, the explosion would not have happened. (But everyone on the crew was undoubtedly taught that going overboard is the last resort due to the threat of pollution. Hmmm…time to rethink that one.)

- If only the crew of the vessel had activated the Emergency Shutdown System in time, an explosion might have been averted.

Ms. Fleytas, 23, had graduated from maritime school in 2008 and had only been on the Horizon for 18 months. This was her first well-control emergency. But she had been trained, she said, to immediately sound the general master alarm if two or more sensors detected gas. She knew it had to be activated manually. She also knew how important it was to get crew members out of spaces filled with gas.

Yet with as many as 20 sensors glowing magenta on her console, Ms. Fleytas hesitated. She did not sound the general master alarm. Instead she began pressing buttons that told the system that the bridge crew was aware of the alarms.

- If only someone had reacted in time to activate the riser disconnect package, thereby freeing the rig from the well, the explosion/fire might have been averted. The presence of the twisted riser still connected to the top of the BOP greatly compounded the complexity of controlling the well.

The recurring theme in these failures is the confusion regarding the chain of command: whose responsibility is it to recognize and react to an emergency? The only right answer is that all hands need to be prepared and empowered to respond appropriately.

Another aspect of human nature is the tendency to react to every situation as if it were routine, even when it clearly is not. It is a lot to ask of a 23 year-old to be the one person out of 130 to pull the ripcord on a million-dollar a day operation.

To put the dilemma facing these rig workers in more familiar terms: imagine you’re driving down the interstate at 70 mph. You look up and see oncoming headlights in your lane 300 yards ahead. What do you do? You have about 4 seconds to decide between slamming on the brakes or “evasive maneuvers”. Any choice you make involves risk, and there are no second chances.

Another interesting bit from the article: it has been widely reported that Transocean had disabled the master alarm from the crew quarters to keep from waking crew members with false alarms. It has not been widely reported, so far as I know, that they did so with the approval of the Coast Guard. What’s up with that, and why is nobody holding the USCG’s feet to the fire?

Cross-posted at VladEnBlog.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member