The voting is over, and so for the most part is the counting. The delegate math, I leave to others; let’s take a look at how the popular vote has shaped up over the course of this primary season and what conclusions we can draw. First, the overall popular vote before Super Tuesday, on Super Tuesday, and to date.* In addition to listing the candidates’ individual vote totals, I’ve classified them in three groups: the five conservative candidates (Santorum, Gingrich, Perry, Bachmann and Cain), the two moderate candidates (Romney and Hunstman) and the libertarian (Paul). While there will undoubtedly be some grousing over the use of those labels, I think it’s uncontroversial to note that Santorum, Gingrich, Perry, Bachmann and Cain all built their campaigns around appealing first to the conservative wing of the party and reaching out from there, while Romney and Huntsman took the opposite approach (and Paul, of course, is in his own category), so this turns out to be a reasonably useful descriptor of how the electorate has broken out between the voters responding to these different appeals. If anything, this overstates the moderate voting bloc, as Romney’s “electability” argument, among other things (including religious loyalties among Mormon voters), has tended in exit polls to draw him some chunk of conservative support.

I. Popular Vote Totals To Date

| Pre-3/6Votes | % | SuperTuesday | % | TOTAL | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romney | 1,831,177 | 40.4% | 1,404,594 | 38.1% | 3,235,771 | 39.3% |

| Santorum | 1,082,820 | 23.9% | 996,305 | 27.0% | 2,079,125 | 25.3% |

| Gingrich | 982,341 | 21.7% | 836,726 | 22.7% | 1,819,067 | 22.1% |

| Paul | 505,760 | 11.2% | 419,499 | 11.4% | 925,259 | 11.2% |

| Huntsman | 52,872 | 1.2% | 13,639 | 0.4% | 66,511 | 0.8% |

| Perry | 29,889 | 0.7% | 13,929 | 0.4% | 43,818 | 0.5% |

| Bachmann | 14,339 | 0.3% | 5,475 | 0.1% | 19,814 | 0.2% |

| Cain | 13,603 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 13,603 | 0.2% |

| Conservatives | 2,122,992 | 46.8% | 1,852,435 | 50.2% | 3,975,427 | 48.3% |

| Moderates | 1,884,049 | 41.5% | 1,418,233 | 38.4% | 3,302,282 | 40.1% |

| Libertarians | 505,760 | 11.2% | 419,499 | 11.4% | 925,259 | 11.2% |

| TOTAL | 4,535,498 | 3,690,167 | 8,225,665 |

There are three obvious conclusions here. One, Romney is steadily outpolling any one of his individual rivals, cementing his frontrunner status. Two, his frontrunner status derives entirely from the division among his opponents: the conservatives have consistently outpolled the moderates. And three, despite winning his home state of Massachusetts by a 60-point, 220,000 vote margin on Super Tuesday and despite none of the conservatives being on the ballot in Virginia, Romney’s not getting any stronger – even with Perry and Bachmann out of the race and Cain not drawing a single recorded vote, the conservatives drew a majority of the votes on Tuesday. Thus, as Romney pulls away in the delegate race and thus advances closer to being the nominee, he does so over the sustained objections of a near-majority faction of the party. More optimistically, the strength of the conservative vote – even in a year when that vote is fractured and underfunded and the remaining conservative candidates are decidedly subpar – bodes well for conservative candidates who can unify that vote in the future.

Let’s dig deeper below the fold:

* – Excluding the Wyoming Caucus, for which the vote totals are minuscule and there’s no comparable 2008 data. Late-arriving votes are still being tallied in some of the Super Tuesday states as well, but the numbers are pretty close to final everywhere. Also, vote totals (including minor candidates) were only available for some states, whereas in others I just added up the people I had data for, thus the totals don’t completely match up.

II. State By State

| STATE | Conservatives | Moderates | Libertarians |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA | 67.3% | 26.2% | 6.6% |

| TN | 62.5% | 28.4% | 9.1% |

| OK | 62.1% | 28.3% | 9.6% |

| SC | 59.0% | 28.0% | 13.0% |

| MO | 57.7% | 25.8% | 12.2% |

| MN | 55.7% | 16.9% | 27.2% |

| IA | 53.2% | 25.1% | 21.4% |

| CO | 53.2% | 34.9% | 11.8% |

| OH | 52.2% | 38.5% | 9.3% |

| ND | 48.2% | 23.7% | 28.1% |

| FL | 46.1% | 46.8% | 7.0% |

| MI | 45.9% | 42.2% | 11.9% |

| AK | 43.4% | 32.5% | 24.1% |

| AZ | 43.2% | 47.3% | 8.4% |

| WA | 34.1% | 37.6% | 24.8% |

| VT | 32.8% | 41.8% | 25.4% |

| NV | 31.1% | 50.1% | 18.8% |

| ME | 24.7% | 38.0% | 36.1% |

| ID | 20.3% | 61.6% | 18.1% |

| NH | 19.7% | 56.1% | 22.9% |

| MA | 17.3% | 73.1% | 9.6% |

| VA | 0.0% | 59.5% | 40.5% |

The conservative bloc has won a majority in nine states, concentrated heavily but not entirely in the South and the caucus states (but including Ohio, where the conservatives drew 52.2% of the vote). Add to that three states where the conservative bloc formed a plurality, including Michigan. By contrast, the moderates have drawn a majority in five states – two New England states, two caucus states with large Mormon populations, and Virginia – and a plurality in five others, including two more New England states and Arizona, which also has a significant Mormon population. Only Florida, where Romney poured vast financial resources into the notorious 65-to-1 ad advantage over Newt Gingrich (the only opponent on the airwaves), did the moderates come close to a majority outside of Romney’s most natural home turf.

III. Primaries vs Caucuses

I’m on record as far back as 2008 believing that caucuses should be abolished, and that the ability to win primaries is much more indicative of general election strength than winning more sparsely-attended and often unrepresentative caucuses. It’s worth examining how the votes break down by type of election:

Mitt Romney, in 2008, was largely a creature of the caucuses; with his money and the unity and organization of his Mormon support, he won eight caucuses while winning only three primaries, in his home states of Massachusetts, Michigan and Utah. That’s been inverted in 2012, although Romney fared much better in the Super Tuesday caucuses than he had before yesterday, undoubtedly owing in part to heavy Mormon support in Idaho and Alaska.

This time around, it’s been Rick Santorum who relied heavily on the caucuses (where he could overcome his financial constraints by relying on cohesive religious conservative communities); although Santorum has broken out of that box in the Missouri, Michigan and Ohio primaries, only in Tennessee and Oklahoma has he won significantly contested primaries. Meanwhile, Newt Gingrich continues to draw nearly twice as much support in primaries as caucuses, reflecting a campaign that is not well-organized and draws on older voters unified by ideology rather than religion. But the real story of the caucuses is Ron Paul, who regularly draws twice as much support in caucus states as primary states, where the larger electorate more easily drowns out his band of committed activists.

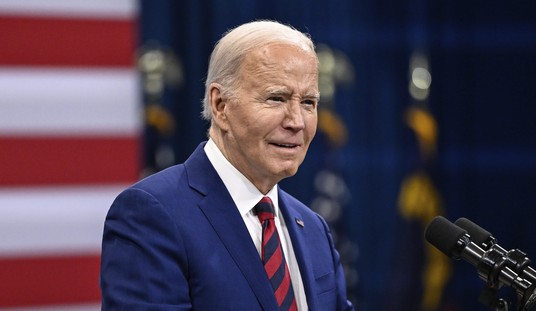

IV. Turnout and 2008 vs 2012

(Click to view full size)

Note here that Idaho switched from a primary in 2008 to a caucus in 2012, dramatically reducing turnout; not coincidentally, it’s the only state so far where Ron Paul drew fewer votes than in 2008. Romney, meanwhile, has seen his vote share vs. 2008 dramatically lifted by his showing in states like Ohio and Virginia that didn’t vote last time until after he had withdrawn from the race. Also note that Washington last time held both a caucus and a primary, which explains why the caucus was much more heavily attended this year. Ohio figures from 2008 are a little iffy because two sets of numbers were reported. What you can see from this chart is that, aside from states where he didn’t run last time. Romney really has only grown his vote totals from four years ago in a couple of states where he went all-out spending money (or, as in South Carolina, where there was a particularly large, up-for-grabs McCain vote). The fact that Romney drew fewer votes than four years ago in ten different states, as the frontrunner against an arguably weaker field, does not inspire confidence.

Overall, turnout has not been impressive outside of South Carolina, Michigan and Ohio and a couple of the smaller electorates. Note that South Carolina was the one state where the conservative vote really came together behind a single, non-hometown candidate; like the fact that Newt’s and Rick Perry’s highest showings in the national polls were the highest of any of the candidates, this is indicative of the fact that there’s a lot of untapped enthusiasm out there for a candidate who can unite and excite the various components of the conservative base of the party. Newt wasn’t able to sustain that any more than Perry was, but there’s no doubt that both pursued a path to the nomination that had a higher ceiling than that of an unexciting moderate or a religious conservative.

V. Where Do We Go From Here?

As I noted at the outset, Romney hasn’t – yet, at least – shown the kind of growing share of the vote that would characterize a frontrunner who is sealing the deal. From here the race moves to Kansas (as well as Guam, the Virgin Islands and the Northern Marianas) on March 10, and Alabama, Mississippi and Hawaii (as well as American Samoa) on March 13; other than Hawaii, these are likely to be much more friendly territory for Santorum and Gingrich than Romney (Paul may do well in Kansas, which holds a caucus). Missouri holds its caucus on the 17th, Louisiana its primary on the 24th. On the other hand, we have two primaries that are likely to heavily favor Romney – Puerto Rico, where he’s been endorsed by popular Governor Luis Fortuno, on March 18, and Illinois, which has a fairly liberal Republican electorate long accustomed to settling for moderates, on March 20. My guess is that we won’t really begin to see momentum – Romney starting to finally pull away in the popular vote, as opposed to winning tight pluralities in competitive states while each candidate wins the states more naturally favorable to them – until we get into the winner-take-all votes in April, partcularly Wisconsin (which should naturally be competitive) and Pennsylvania (which should naturally heavily favor hometown favorite Santorum).

Is that a good thing? I think thus far, it’s been important for the primary to keep going, because (1) until yesterday, there remained a path to victory for other candidates, and the voters need to know that the race won’t be ended prematurely by backroom deals rather than by acts of the voters, (2) it forces Romney to work for conservative support and become a better candidate, and (3) it sends a message to the party establishment that Romney-style candidates who are long on money and short on reliable principles will not go down without an expensive and laborious fight.

Like Erick and Neil, I think Romney’s narrow wins in Florida, Michigan and now Ohio have cemented him in a position where it’s all but certain that he’ll be the nominee, and as I said before, I think Michigan was the last hope for a new entrant in the race. For reasons (2) and (3) above, I don’t see a lot of harm in continuing the campaign through the rest of March until we are 100% certain of that fact, as it gives additional states the chance to register their objections to the frontrunner and put Santorum through the final paces of seeing if he can find one last way to knock Romney off his pedestal. Newt, despite gaining some delegates yesterday and a moral victory in his home state of Georgia, no longer has much to accomplish in this race besides a protest candidacy.

There’s a three-week break between the April 3 primaries in Wisconsin, Maryland and DC and the next set of primaries. My guess is that if Romney can win Wisconsin, it will be a lot harder for Santorum to justify continuing, and if he folds his tent, Newt and Paul will no longer have a race to show up for. Given how Wisconsin has been Ground Zero for many of the leading political battles of the past two years, that could be the real end of things, and if not, it will come with Pennsylvania, New York, Rhode Island, Delaware and Connecticut on April 24.

But whenever the verdict of the delegate race becomes final, the voters have already spoken, and their message is clear: this is still the conservatives’ party, awaiting only the right leader to unite it.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member