The opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of RedState.com.

One of the most egregious aspects of American criminal justice is the fact that men with guns and badges are legally allowed to steal the property of American citizens, leaving their victims without legal recourse, in many instances. Civil asset forfeiture has been a hotly-debated issue despite not receiving much attention in the national spotlight. But, it remains one of the most brazen violations of our rights.

Civil asset forfeiture is a practice that permits police officers to seize money and property from an individual who is suspected of having committed a crime – even if they have not yet been charged with an offense. Indeed, many of those on the receiving end of this policy are never charged or convicted, but are still unable to retrieve their property after the government steals it.

The rationale behind this practice is the notion that property can be charged with an offense, even if the person who owns it has not been charged or even convicted. Proponents argue that this ability is critical to the efforts of law enforcement to crack down on crime.

Critics point out that the practice is corrupt. It motivates police officers to search for, or concoct, a pretext to stop people and search their vehicles, which is a blatant abuse of authority. If they find large sums of money or other valuable property, they can claim it came from the proceeds of drug trafficking or other crimes and keep it for the government. People have referred to this as “policing for profit.”

This practice finds its origins in medieval England, according to a piece by Brittany Hunter for The Foundation for Economic Education, when the British Crown could confiscate weapons used to commit murder. The law held that the government would charge the object with murder, and it would typically sell the item and give the proceeds to charitable organizations. But over time, the Crown began to keep the money for itself.

Later, the British Crown used this practice to steal money and property from American colonists to fund its war chest. Indeed, it was one example of tyranny that led to the American revolution. Turns out that the colonists weren’t on board with having their government pilfer their earnings and were willing to take up arms to put a stop to it.

Hunter noted:

The Navigation Act of 1600, part of the broader Navigation Acts, mandated that any ship bringing cargo into the “New World” had to first go through British checkpoints for inspection. Additionally, any cargo ship leaving the American colonies with goods was also required to be checked before continuing on to its destination. The purpose of these inspections, of course, was to ensure that the Crown got its cut of the loot.

If, for example, someone attempted to skirt the rules by shipping cargo to another country without first stopping through Britain, they were deemed “smugglers” and “pirates” trying to avoid taxation and left themselves open to having their cargo—and even the horse and buggy used to load the goods onto the docks—confiscated. As subjects of the crown, the British authorities had expected the colonists to help enforce the Navigation Acts from afar. However, the colonists were not so eager to enforce the abusive policies of a distant government.

As it turns out, the American government was no better. It enacted its own form of asset forfeiture as a pretext for stealing money and property. The main difference is that the new government used this practice during times of war, having levied hefty taxes through customs duties on cargo ships. Naturally, some tried to avoid paying these fees and were labeled as “pirates” and “smugglers.” The U.S. government enlisted privateers to hunt down those who had not paid their customs duties and seize their property.

Later, the U.S. government expanded the practice through the war on drugs. Under various drug laws, law enforcement was empowered to collect money and securities believed to have been used in the perpetration of drug-related crimes.

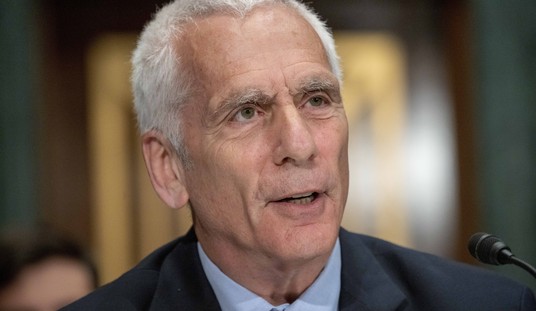

Those who favor civil asset forfeiture argue that it helps law enforcement fight crime by depriving criminals of the resources used to perpetrate crimes. But, critics argue, that it is nothing more than a revenue-generating scheme. Many have criticized policing for profit, including Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

In the case of Leonard v. Texas, he laid out his case when writing his opinion. He noted that “unlike a criminal case in which a prosecutor must prove a defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, in a civil forfeiture case, the prosecutor only needs to establish the basis for the forfeiture by a preponderance of the evidence.”

He continued:

Fourth, also unlike a criminal case in which the prosecutor must prove that the person who used or derived the property acted intentionally or at least was willfully blind to its misuse, in a civil case, the government does not have to prove any of that. Rather, the burden is placed on the “innocent owner” to prove a negative: that he did not know about its illegal use and that, if he did know about it, he did all that could reasonably be expected under the circumstances to terminate such use.

It is also important to note that in cases involving policing for profit, it is rare that the victim is able to regain the money or property stolen by the government. The process through which one can reclaim their belongings is often complex, requiring the aid of an attorney, in most cases.

Oh, and lest we forget, even though the state is alleging the property was used in a crime, the victim is not entitled to an attorney in these matters because the action is against the property, not the person. So, one would have to spend hefty sums of money to hire a lawyer to help them navigate the process. Since most can’t afford the attorney’s fees, they are helpless to fight against the system.

State governments have raked in tons of cash from civil asset forfeiture. In 2017, Texas’ law enforcement took in about $50 million, which included people who were not charged or convicted of a crime. Since the state’s attorney general does not distinguish between the two when calculating the numbers, it is not known exactly how many were never charged. Since 2000, state and federal governments have taken at least $68.8 billion, according to the Institute for Justice.

Even more egregious is the fact that despite the contention that stealing money and property aids law enforcement in stopping crimes, the practice has not been proven to be effective. According to the Institute for Justice, the clearance rates for violent crimes tends to drop as the amount of forfeiture revenue increases. This Is largely due to the fact that when police are hunting for cash drug offenders, they are not as focused on addressing violent criminals. Moreover, the practice has not led to a decline in drug use in communities in which it is used.

Some states have passed legislation severely limiting the use of civil asset forfeiture. There is a growing movement to curb this practice. Hopefully, governments will no longer be allowed to abuse its citizens by stealing their property.