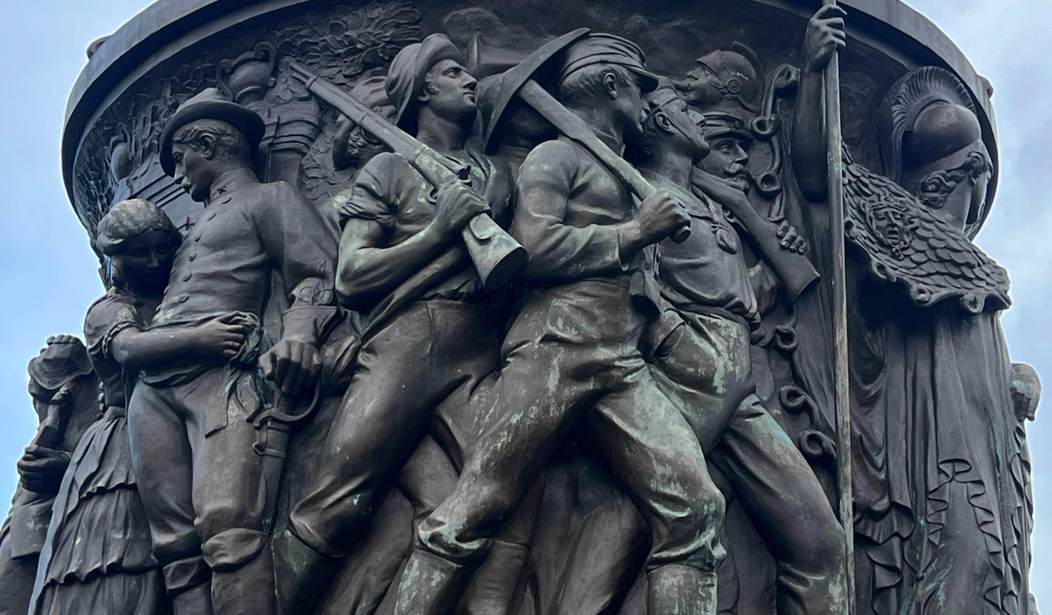

The attorney representing the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a Massachusetts native with ancestors who fought on both sides of the Civil War, told RedState despite the Army’s accelerated deconstruction of Arlington National Cemetery’s Confederate Memorial and repeated legal setbacks, the fight to save the monument is not a lost cause.

“There’s potentially a legal solution or potentially a political solution,” said H. Edward Phillips III, who is based in Franklin, Tennessee.

Phillips said he filed motions Dec. 21 that acknowledge that the Army and its contractor hurried the removal of the memorial’s bronze program and statue, created by sculptor Moses Ezekiel, that request the court ensure that the bronze elements be adequately stored and protected, anticipating their return to Arlington.

Ezekiel, whose grave is at the base of the monument, joining the more than 400 Confederate graves placed on concentric rows surrounding the memorial, also known as the Reconciliation Monument, was himself a veteran of the 1864 Battle of New Market, fighting with more than 200 of his fellow Virginia Military Institute Keydets.

The Long Island, New York, native said in addition to the legal actions by the SCV, another group, Defend Arlington, is continuing its lawsuit being heard by federal Judge Rossie David Alston Jr., appointed to the bench by President Donald J. Trump.

Monday, Alston granted a stay blocking the Pentagon from tearing down Ezekiel’s bronze sculptures until Wednesday, when he would hold a hearing on the concerns raised by both SCV and Defend Arlington that the Army and its contractor Team Henry Enterprises did not take the necessary precautions to protect the graves.

Team Henry is owned by Devon Henry, who has become the left’s go-to destroyer of Confederate memorials. He was the man who took down Gen. Robert E. Lee’s statue from Richmond, Virginia, in addition to more than two dozen other war memorials in Virginia and North Carolina.

In a Dec. 15 letter to https://twitter.com/Rep_Clyde, the Capitol Hill leader of the movement to preserve the war memorial dedicated by President T. Woodrow Wilson, in 1914, Army Secretary Christine E. Wormuth told Clyde that the Army would transfer the bronze to the Commonwealth of Virginia.

On Friday, the Secretary of the Army responded to our letter.

— Rep. Andrew Clyde (@Rep_Clyde) December 18, 2023

Sec. Wormuth confirmed that the Army will remove the Reconciliation Monument by the January 1, 2024 deadline. pic.twitter.com/enN4EQLMxk

Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin negotiated the transfer to Virginia, and the plan is to exhibit the bronze at the commonwealth's New Market Battlefield State Historical Park.

Phillips said he understands why some people are satisfied with the Youngkin plan, but it is SCV's position that it is unacceptable.

“None of us want that,” he said. “The reason why is because Virginia's monument protection law was gutted by the Democrats in 2020.”

The attorney said that Virginia’s laws did nothing to protect other Confederate memorials, and if a Democrat succeeds Youngkin, who is limited to one four-year term, there is no recourse.

“If a radical comes in that monument is up for grabs in terms for destruction,” he said. “I think it's highly inappropriate to give it to the Commonwealth of Virginia.”

The designation of the monument as a grave marker or not is critical because the Pentagon’s Naming Commission, charged by Congress with the task of removing all traces of the Confederacy from Defense Department assets, ordered the removal of the bronze before Jan. 1, but was forbidden by Congress to disturb graves or grave markers.

This prohibition from disturbing grave markers led the Army, which operates the cemetery, to remove the bronze but leave the unadorned stone base.

Although defenders of the monument thought they had a hearing Wednesday, Alston visited the site himself, then moved the hearing to Tuesday and revoked his stay, which was scheduled to expire at the close of business the day of the Wednesday hearing.

“It’s unusual the judge would conduct his own investigation,” the attorney said. “I think that's fair to say—and it's not a recrimination on the judge, but it's just one of those things where it is very unusual.”

He said he heard the judge spoke to the workers at the site.

“I've heard various sources, so I'm not sure exactly what happened, but one of the things that I heard was that he spoke to the folks from the Army and everything else,” he said.

“To have kept this even, I think what he should have done, if he wants to go out and see the site, for example, it happens in jury trials," he said. "Have both parties with the judge."

Neither SCV nor Defend Arlington were told about the judge’s site visit in advance, he said.

“Whether the judge wants to believe or not or wants to believe anybody or not, the artist--Moses Ezekiel--his footstone is two feet away from the base of the monument,” he said.

He said that because of the close proximity of Ezekiel and other graves to the monument, the commission directed that workers put down some type of platforming during the work.

“You really need to put up steel planking over these graves to ensure that they're not trampled on, but they never put up the steel planking, no wood planking, nothing,” he said.

“By the time the judge got there, I heard everything was kind of cleaned up, and you couldn't see any traces of anything," he said.

“By the time the judge got there, I heard everything was kind of cleaned up, and you couldn't see any traces of anything," he said.

The deconstruction was scheduled to begin Monday and done through Saturday," he said. The work was complete by Thursday.

“They didn't have the opportunity to be there with the judge and make sure that it was pretty much a neutral setting—I’m not in any way casting aspersions on the judge,” he said. “From my perspective, this judge made his decision—he said nothing influenced him other than what was before him on the allegations and the pleadings.”

On the political side, Phillips said Congress could clarify that the Confederate Memorial was indeed a grave marker.

“If we prevail on the merits, one of the remedies is that you have to put this thing back up because this was incorrectly classified by the naming commission,” he said.

“It's actually a grave marker, and it should go back up.”

Editor's Note: A prior version of this article referred to Mr. Phillips as a Southbridge, Massachusetts native — although Mr. Phillips spent over 18 years in Southbridge, he was born on Long Island, New York. We have updated the piece to reflect that and apologize for the error.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member