As we reported earlier, the Supreme Court issued a much-anticipated ruling today dealing with the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. In the case of Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, the Court held that the policy of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, which prohibited participation in the State’s Scrap Tire Program by churches, sects, or religious entities, violated the rights of the Church under the Free Exercise Clause. Denying the Church an otherwise available public benefit due to its religious status amounted to putting Trinity Lutheran to the following choice: “It may participate in an otherwise available benefit program or remain a religious institution.”

The program in question offers qualifying nonprofit organizations grants for installing playground surfaces made from recycled tires. Pursuant to Article I, Section 7 of Missouri’s Constitution (commonly referred to as the state’s “Blaine Amendment”), the DNR “had a strict and express policy of denying grants to any applicant owned or controlled by a church, sect, or other religious entity.” Thus, although the Church qualified for the program — and was, in fact, ranked fifth out of the 44 applicants for the year in question — its application was denied by the DNR. The Church filed suit in the United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri, which ruled in favor of the State, as did the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Shortly before the Supreme Court heard oral argument in the case, Missouri’s Governor, Eric Greitens, announced that he was directing the DNR to cease its previous policy and to begin allowing religious organizations to compete for the DNR grants. Nevertheless, the Court proceeded to hear and rule on the case, finding that this policy change did not render the matter moot, as it could just as easily be reversed. The Court addressed this in Footnote 1, but it is Footnote 3 which appears to be a sticking point for several of the justices. While the decision was 7 to 2, Justices Thomas and Gorsuch took issue with the Court’s caveat that:

‘This case involves express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing. We do not address religious uses of funding or other forms of discrimination.”

Both Thomas and Gorsuch found this a bit too narrow. Thomas, in his concurrence, took issue with the Court’s reliance on a 2004 Free Exercise case, Locke v. Davey, as he joined Scalia in dissent on that one. In his concurrence, Gorsuch first explained his concern regarding relying on a distinction between religious status and religious use to distinguish the holding in Locke, as a line which might too readily be blurred. He then points out that, while Footnote 3:

“Is entirely correct…I worry that some might mistakenly read it to suggest that only ‘playground resurfacing’ cases, or only those with some association with children’s safety or health, or perhaps some other social good we find sufficiently worthy, are governed by the legal rules recounted in and faithfully applied by the Court’s opinion. Such a reading would be unreasonable for our cases are ‘governed by general principles, rather than ad hoc improvisations….’ And the general principles here do not permit discrimination against religious exercise — whether on the playground or anywhere else.” (Citation ommitted.)

Justice Breyer also filed a concurring opinion, in which he noted “no significant difference” between this program aimed at improving the health and safety of children and other general government services, such as police and fire protection. He points out that cutting off religious schools or other entities like Trinity Lutheran from such services clearly is not the purpose of the First Amendment.

In setting forth the Court’s rationale for the decision, Chief Justice Roberts has some encouraging observations for those who prize the First Amendment and, in particular, religious liberty:

“The express discrimination against religious exercise here is not the denial of a grant, but rather the refusal to allow the Church—solely because it is a church—to compete with secular organizations for a grant….Trinity Lutheran is a member of the community too, and the State’s decision to exclude it for purposes of this public program must withstand the strictest scrutiny. (Citation ommitted.)

….

“The Missouri Department of Natural Resources has not subjected anyone to chains or torture on account of religion. And the result of the State’s policy is nothing so dramatic as the denial of political office. The consequence is, in all likelihood, a few extra scraped knees. But the exclusion of Trinity Lutheran from a public benefit for which it is otherwise qualified, solely because it is a church, is odious to our Constitution all the same, and cannot stand.”

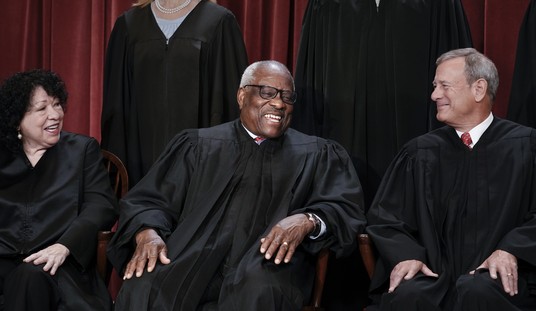

Then we get to the dissent, penned by Justice Sotomayor (and joined by Justice Ginsburg.) In her dissent, Sotomayor opined that:

“The Court today profoundly changes [the relationship between church and state] by holding, for the first time, that the Constitution requires the government to provide public funds directly to a church.”

I haven’t yet had the opportunity to read the entire dissent, but I question Sotomayor’s characterization of the decision. Disallowing the exclusion of a religious organization from a public benefit solely because it is a church profoundly changes the church-state dynamic?!

Shortly after it was handed down, I had the opportunity to speak with Carrie Severino, chief counsel and policy director of the Judicial Crisis Network, and inquired as to her take on Sotomayor’s contention. She called it “nonsense,” and pointed out that Sotomayor’s own opinion makes it clear that historically, there have been far greater instances of involvement between church and state which have been upheld.

Ms. Severino expressed little surprise at the ruling, as it was consistent with the justices’ questioning during oral argument. A big takeaway from this ruling, she believes, is that it, combined with the ruling last week in Matal v. Tam, are encouraging signs that this Court is still very committed to the First Amendment and holding firm on the notion that the government should not be in the business of picking and choosing between religious groups or viewpoints. To that, I say, “Amen!”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member