When World War II began, my father went to enlist in the Marines. Not surprisingly, he was rejected. He had sight in only one eye.

Dad was a new American citizen. Also determined. So, he memorized the eye chart and went back a few weeks later. Alas, it was the same doctor. Dad rattled off the eye chart, perhaps a little too quickly.

The doctor grew suspicious. “Okay,” he said, “Now, read it backward.”

Dad failed. “What would happen if you got shot in your good eye?” the doctor asked.

Dad’s reply, “The same thing that happens to anyone shot in the eye.”

With so many men away at war, Dad became the neighborhood husband-father, available to do the things that absent husbands would normally do.

At the time, I didn’t really wonder why neighborhood kids got wooden Christmas toys just like the ones Dad made for me.

It was a different time to be a child or have one. Safe civilian life seemed normal, unremarkable, until I experienced later eras.

The big fear during that war and then the Korean War seemed to be spotting a Western Union messenger come down the street. Soon after, all the wives descended on the house where he had delivered the government telegram.

At age 5, my first day of kindergarten, Mom walked me the five city blocks to school. On the next day, four blocks, then three, and two. The second week, I was on my own. Seemed perfectly normal.

Things have changed. In politics, too.

It’s hard now to remember a time when we had a president that most people genuinely liked. There's always controversy. But now there's more suspicion, conspiracy theories, less personal.

Before, it was more about agreeing or not with policies, not the visceral and verbal hate toward a POTUS that we now experience through so many more forms of instant media. There, anonymity protects the most vitriolic posters.

As a Wall Street Journal op-ed recently observed:

The sad fact seems to be that we haven’t had an American president that the country has been able to feel good about for more than half a century.

I first became aware of presidents when I saw the shock over Harry Truman’s 1948 upset election.

We want these men to be national symbols of strength, right, and unity, not unlike a temporary king who gets elected, rules with restraints, and then gets discarded for someone new, now and then. These men are human, sometimes very human. Also pretentious, even petty. Often inauthentic. In other words, just like most everyone, except they work on a public stage with hostile or sympathetic media coverage.

Wise, tough, experienced commanders in chief who can deal with serious strategic and life-and-death decisions about when to use force and when not to against adamant adversaries.

But they’re also expected to handle the ceremonial crap like dutiful grandfathers, to preside over Easter Egg rolls, to witness the fireworks as joyously as we do, to change sides halfway through the Army-Navy game, to watch the Super Bowl with snacks and to remember the vice president’s name.

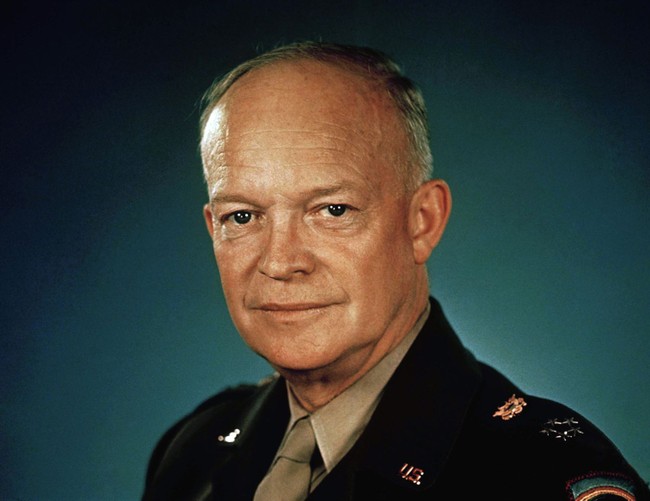

It’s impossible to be perfect, of course. In my life experience, Dwight Eisenhower came the closest with eight years of peace and, you felt, principle. None of his brothers were selling influence abroad with money pouring into shell companies stateside. Ike’s wife didn’t have to lead him around.

Party conventions were first televised in 1952, both from the same Chicago site. During the roll call of states, my Dad had me recite the next one in alphabetical order.

Ike knew war up close as allied commander in Europe when I was playing on the rug with wooden letters and cars.

He ended the stalemated Korean War. He resisted a French invitation to join the fight against Ho Chi Minh’s Communists in what became North and South Vietnam.

Barack Obama, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, joined France and Britain in 2011 to oust Libya’s leader, which created another worrisome lawless state. Eisenhower also declined to join the 1956 British-French invasion of Egypt to seize the Suez Canal.

Ike did send federal troops into the South to enforce school desegregation, just as fellow Republican Ulysses Grant sent federal troops into the South to enforce voting laws after the Civil War.

Many probably know that Ike’s administration launched the now-essential Interstate system in 1953. The idea of a vast, inter-connected, nationwide network of super highways uniting the U.S. was actually 34 years old.

It was first proposed in 1919 by an Army colonel who took a convoy cross-country to document the state of the nation’s road infrastructure.

It was awful – dirt roads without names or numbers, signs, directions, maintenance, or coordination. It took him a month. The colonel's report was shelved as too grand. The report’s author was Col. Dwight Eisenhower.

He knew the original purpose of interstates was for defense to ease military movements in an emergency because France’s military had been crippled by poor roads in the first world war. But he also knew it would facilitate commerce.

Perhaps you’ve noticed long stretches of straight Interstate pavement outside urban areas. They’re not just for making good time. Those are also planned runways too numerous to all be disabled by an enemy.

In 1961, John F. Kennedy came into office as a breath of youthful fresh air, energy, and promise. Four months after he wore a top hat to his inauguration, Kennedy dispatched the first U.S. troops to counter the communist insurgency in Vietnam.

His traumatic assassination brought in Lyndon Johnson. Like most vice presidents, he was picked for a strategic political reason called Texas. Nothing else.

Democrats do love senators though – Kennedy, Johnson, Humphrey, McGovern, Mondale, Gore, Kerry, Edwards, Obama, Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, Kamala Harris.

Johnson prosecuted the deadly war with the vigor and determination of a former Senate Majority Leader accustomed to driving an obedient political herd.

He didn’t get obedience. So, he pressed harder and harder. His congressional cajolery proved ineffective with mounting body counts – 58,220 Americans by the end. And 1,224 are still missing.

I covered some of the war protests and worked at the riotous 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. The 1960s were more than just fractious and angry.

They were deadly, especially the Johnson presidency, the racial riots, and political assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., the attempted assassination of George Wallace, and related bombings. They left emotional scars, I suspect, on everyone who experienced those divisive days, myself included.

I was in Vietnam near the war’s end in 1975, and reported from the region afterward. Gerald Ford, a combat veteran like all modern presidents until Bill Clinton, inherited the presidency when Richard Nixon resigned.

I’m not sure exiting any military theater in defeat without a formal surrender could ever be well-organized after years of investment in training, materiel, money, manpower, and blood.

But the panic inflamed by the secret suddenness of withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975 was the tragic precursor to a similar ad hoc exit by Joe Biden from Afghanistan in 2021.

Without any military background, the oldest president ever overrode Pentagon advice and plans, left billions in modern military gear behind, and abandoned thousands of Afghan allies and green-card holders to the murderous mercies of the Taliban. He still calls that debacle an “extraordinary success,” though it ignited the steep decline in his job approval.

As a senator, Biden was renowned as a goofy, garrulous fabulist who would forever rank near the bottom of any academic class. All presidents presumably tell what Mark Twain called ”stretchers.”

Obama, for instance, has never explained his 16-hour disappearance during that deadly 2012 night in Benghazi. And he publicly promised 37 times that Obamacare would not affect anyone’s ability to keep their doctor or health plan.

But Biden’s record on veracity has taken lying to new depths.

That and his clearly declining mental and physical health have combined to give Shuffles the worst job approval of any modern president at this stage. One recent poll asked what was Biden's greatest achievement. The most common answer: "Nothing."

For chapter and verse on this, please peruse my colleague Nick Arama’s Author page.

As one measure of change over the years, if Gallup had a Presidential Scale of Scary, Dwight Eisenhower wouldn’t qualify to be on it. Joe Biden would rule atop it.