The Rise of the Bolt-Action Sporter - The Big Two – Remington and Winchester

Previously on RedState: Sunday Gun Day XXIX - The History of Bolt Guns, Part I

Sunday Gun Day XXX - the History of Bolt Guns, Part II

Sunday Gun Day XXXI - The History of Bolt Guns, Part III

Sunday Gun Day XXXII - The History of Bolt Guns, Part IV

OK, enough war stuff. Let’s have some fun.

When it comes to 20th-century, bolt-action sporters in the American market, it’s fair to say that you can list them in three categories: The Winchester Model 70, the Remington 700, and everything else. There’s more to the shooting world than that, of course, so this time out we’ll look at those three and some non-U.S. models as well.

Remember the Pattern 14 and 17 Enfield rifles, built by American manufacturers for the British and American armies? It should come as no surprise that, having tooled up to build those Mauser-style actions, the two major American rifle builders would use that action for their first round of bolt-action sporters.

As we have previously noted, Remington was first with their Model 30 sporter, initially offered in .30-06 and later in other calibers. What is less known is that Winchester dabbled in a sporter based on the Pattern 17 action as well.

The Winchester Model 51 “Imperial” rifle was a hand-made, carriage trade piece. Only 24 were made in 1919, in .30-06, .35 Whelen, and “.27 caliber,” a forerunner of the .270 Winchester. Four of these were hand-made pre-production prototypes, with the remaining 20 being hand-made Gunsmith Shop items.

I’ve long lusted after one of these first Winchester bolt-action sporters, but I doubt one will ever appear at a price that I could manage without resulting in my wife phoning a divorce lawyer. The very first of these, Serial Number 1, a take-down version in .27 caliber, just sold in November 2018 at auction for $24,675. So, I doubt one of these 24 rifles will be gracing my gun safe any time soon, and that’s a pity.

Here’s where it gets interesting. One of Winchester’s VPs at the time was a fellow named Frank G. Drew, a staunch proponent of lever guns who considered the very idea of a bolt action sporter to be a trifle silly. He had some influence on the Board of Directors, who canceled the Model 51 project in 1920.

That didn’t last, obviously. Drew became the President of Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1924. He observed the success competitor Remington was having with their bolt-action Model 30, and so caused the development of another Winchester bolt gun, also made with the leftover machines and tooling used in the Pattern 17 actions and the Model 51. This new, more economical mass-produced repeater was the Model 54 Winchester, manufactured from 1925 to 1930, and offered in the .22 Hornet, .220 Swift, .250-3000 Savage, .257 Roberts, .270 Winchester, 30-30 Winchester, .30-06 Springfield, 7x57mm Mauser, 7.65x53mm Argentine, and 9x57mm Mauser. The Model 54 retained the Pattern 14’s heavy, two-stage trigger and had a factory bolt handle and safety that made scope mounting awkward. Primary production on the Model 54 ended in 1930, although a few were assembled from 1930 to 1935.

Happily, in 1936, Winchester improved on the Model 54 when they brought out their immortal Model 70 in 1936, based on a cock-on-open, Mauser 98-type action. Aptly known as the Rifleman’s Rifle, everything a sportsman could want in a bolt-action rifle can be summed up in these words: “Pre-64 Model 70.” Chamberings from 1936 to date have included the .22 Hornet, .222 Remington, .223 Remington, .22-250 Remington, .223 WSSM, .225 Winchester, .220 Swift, .243 Winchester, .243 WSSM, .250-3000 Savage, .257 Roberts, .25-06 Remington, .25 WSSM, 6.5×55mm, .264 Winchester Magnum,6.5mm Creedmoor, .270 Winchester, .270 WSM, .270 Weatherby Magnum, .280 Remington, 7mm Mauser, 7mm-08, 7 mm Remington Magnum, 7mm WSM, 7mm STW, .300 Savage, .30-06 Springfield, .308 Winchester, .300 H&H Magnum, .300 Winchester Magnum, .300 WSM, .300 Weatherby Magnum, .300 RUM, .325 WSM, .338 Winchester Magnum, .35 Remington, .358 Winchester, .375 H&H Magnum, .416 Remington Magnum, .416 Rigby, .458 Winchester Magnum, and .470 Capstick. A great variety of grades and finishes have been available; the U.S. Army and Marines have used Model 70s as sniper rifles (Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock used a Model 70 Winchester in .30-06 with an 8x Unertl scope in his famous exploits in SE Asia.)

In 1964 Winchester’s cost-cutting measures affected the Model 70 as it did many other arms. The big Mauser claw extractor was replaced with a hook extractor, along with other manufacturing and cosmetic changes, including the adoption of a simple push-feed action over the old controlled feed; note that Remington rifles had been using a push-feed design for decades by this point, but the various changes resulted in the Marines canceling their contract for Model 70 sniper rifles, as the new Winchesters no longer met the Corps’ quality standards. The “classic” Model 70 was reintroduced in 1999 with the controlled feed restored, but at least in the mind of this old gun crank, if you want a Model 70, look for a pre-64.

The Model 70 still has turned in a long and impressive history. Shooting Times magazine in 1999 named it the “Rifle of the Century,” and it’s hard to dispute that assessment. No less a famous gun writer than Jack O'Connor favored the Model 70, being one of the Rifleman's Rifle's strongest advocates.

Remington, though, was likewise producing a classic. Their Model 30 rifles were manufactured until 1940 (from 1926 to 1940 as the Model 30 Express, mounting a Lyman peep sight). In 1940, Remington introduced the final version of a rifle on the Pattern 17 action, the Model 720, which changed to a cock-on-close operation.

About 26,000 Model 20 and 30 Express rifles were built, but only about 2,500 Model 720s. World War 2 interrupted Remington’s production, but in 1948 the Ilion gunmakers came out with two new rifles, really one design in short and long action versions; these were the Models 721 (short action) and 722 (long action).

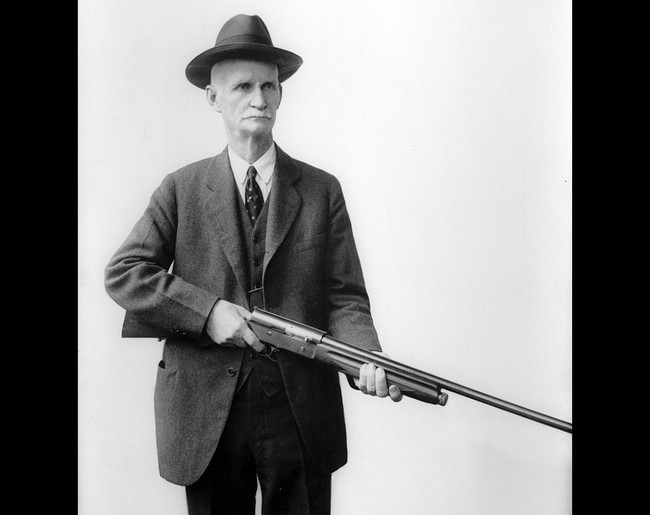

During the Second World War, Remington’s experience with mass-producing weapons quickly and efficiently taught their engineers some great lessons. Two of these engineers were a pair of prescient fellows named Mike Walker and Homer Young, who took a look at the traditional Mauser-style action, machined from a forged billet, and came up with another idea: A tubular receiver was easier and quicker to produce, while still allowing great strength and precision. The 721 and 722 were the first products of this design, followed in 1958 by the Model 725. All were push-feed guns with the usual fixed box magazine, a small hook extractor, and a spring-loaded plunger ejector.

In 1961, Walker and Young’s basic design evolved into one of the best-selling sporting rifles in history, the Remington 700, still manufactured today in a wild variety of calibers and configurations. The 700 has a great reputation for strength, accuracy, and reliability, leading to its adoption by military and police forces all over the globe. My hunting partner and loyal sidekick, Rat, carries one in the game fields, a pre-1993 DuPont Model 700 wearing a Six Enterprises fiberglass stock and a Redfield scope, and has had good success with it.

While my personal preferences lean towards older Winchesters, a beginning, intermediate, or experienced shooter or sportsman simply couldn’t go wrong with a Remington 700. No matter your desires in caliber or trim, it’s probable even in the late 20th century, that Remington made a 700 that matched them.

Remington then took a different tack in 1967, introducing the economical Model 788. This was a nine-lug, rear-locking, short action bolt gun with a plain stock and a 3-round detachable box magazine, available in calibers from the .222 Remington to the .308 Winchester. This rifle had a great reputation for accuracy, supposedly in part from the fact that the rear-locking bolt eliminated the locking lug raceways, making the action stiffer and stronger.

Remington and Winchester dominated the 20th-century bolt gun world, but they weren’t alone. While the Model 70 and the various Remington models were being admired by the shooting press, some other American companies were learning the bolt gun angle as well.

The Other Guys

We have discussed Savage Arms before in the context of their excellent Model 99 lever gun, but Savage learned the art of building bolt guns in World War 2 when they built #4 Mk I Lee-Enfield rifles for the British. With this experience under their belt, Savage rather belatedly turned to the bolt gun market in 1950, with the economical Savage 340. This rear-locking rifle had a plain hardwood stock and a detachable box magazine and was available only in lower-performance rounds like the .22 Hornet .222 and .223 Remington and the .30-30 Winchester.

The 340 was serviceable but was nothing much to look at, but Savage had a more lasting impact on the bolt gun in 1958, when their engineer Nicholas Brewer devised and (posthumously) patented the rifle that became the first of the Savage 110 series. While lacking some of the polish of Winchester’s and Remington’s offerings, Savage rifles proved solid and reliable, and because of that, when Winchester closed their New Haven plant in 2007, the Savage 110 surpassed the Winchester Model 70 as the oldest continuously manufactured bolt-action rifle on the American market. Another fact of note; in 1959, the Savage 110 became the first American bolt-action rifle to be commercially produced in a left-handed version.

About this same time, an Ogden, Utah, gunmaker of note, the Browning Arms Company, entered the commercial bolt gun market with the High-Power series of rifles. The story of the Browning High-Power bolt guns is a complicated one, with the larger calibers (up to the .458 Winchester) on FN 98 Mauser actions, while the smaller rounds like the .222 were set up on the Finnish SAKO action.

The High-Power Brownings were beautiful pieces. The FN Mauser and the SAKO actions were finely made, the bluing was high polish, stocks were fine European or American Claro walnut. Three grades were available, Safari, Medallion, and Olympian, featuring progressively nicer finishes and fancier wood.

But the High-Power, beautiful as it was, suffered from two flaws: A cheap plastic buttplate and too much drop at the heel of the stock, which made recoil unpleasant, and thin barrels that heated quickly and resulted in less-than-optimal accuracy. The High-Power was replaced in 1978 or so by the Japanese-made push-feed Browning BBR, which yielded only mediocre sales. But then, in 1984, Browning introduced the A-bolt, with three locking lugs and a short sixty-degree bolt throw. This was at last a bolt gun fully worthy of the Browning name, fast in action, reliable, and accurate. The A-Bolt has been made in calibers from .223 Remington to .458 Winchester and is still being made as the AB3 today.

Colt may be best known for handguns and the AR-pattern rifles, but in 1973, Colt struck an agreement with the famous Austrian manufacturer, and the Colt/Sauer rifle was introduced to the American market. This was the Sauer Model 80 on the European market and Colt merely imported it, but the Colt Sauer rifle was unique in one respect: It had a non-rotating bolt with retracting locking lugs, which removed the necessity of locking lug traces in the receiver. This not only made for a strong receiver but also for a very smooth action. Even so, the Colt/Sauer rifle never really caught on competing against the Remington 700 and (even the post-64) Winchester 70; in the end, only about 27,000 were imported.

One cannot talk about the 20th-century sporting gun market without mentioning Ruger, and the bolt gun market is no exception. In 1968, Bill Ruger had a designer working for him who took the Model 98 Mauser action, replaced the forged receiver with an investment casting, replaced the bolt block safety with a tang safety, and replaced the blade ejector with a plunger ejector. Sullivan also redesigned the trigger and used a rather novel, angled front action screw that, in recoil, served to seat the action more solidly into the stock. Bill Ruger approved of the design, and the original M77 Ruger was born.

But Ruger wasn’t done. In 1991, the company almost completely redesigned the M77 as the Mark II, retaining the Mauser-style claw extractor but reverting to a Mauser blade-type ejector, converting to controlled-feed rather than push-feed and changing to a Winchester 70-style fore-and-aft safety that allowed for loading and unloading the rifle with the safety engaged.

I have never owned an original M77, but I have a Mark II in the “T” configuration, with a heavy laminated target stock and a 26” heavy sporter barrel, firing the .243 Winchester; this is a rifle that will send a 6mm pill 400 yards on time and on target. My wife has a Mark II Compact in the .260 Remington, a fine, lightweight, light-recoiling little rifle.

These were and are the major players, but few American companies didn’t take a swing at the bolt gun market. Mossberg has produced a few; Smith and Wesson imported some Howa rifles from Japan and slapped the S&W name on them. Even lever-gun maker Marlin has produced a bolt gun. The bandwidth allowed to me here simply won’t allow me to list them all, so I’ve tried to name the major players in the American centerfire bolt gun market.

Before anyone mentions my omission of Roy Weatherby, I would refer you to the piece I've already written on that great American riflemaker.

See Related: Sunday Gun Day XIX - The Marvelous Mr. Weatherby

The Europeans

Continental European sporting bolt guns in the 20th century can, in large part, be summed up, like a popular candy, by saying simply “M&M.” Mauser and Mannlicher. Some Finnish upstarts got into the mix, and an Austrian company also got involved. But across the Channel, the Brits were turning out some real masterpieces.

Mauser suffered badly at the end of World War II, for reasons which should be apparent. But in the early 1950s, they managed to reform, and one of their first offerings was a design by a fellow named Walter Gehmann, which became the Mauser 66. The 66 couldn’t have departed much further from its Model 98 predecessor; it had an odd telescoping bolt and a set trigger, and came as a take-down rifle for easy transport. To my thinking, it wasn’t an attractive rifle, but folks who have handled them (I’ve not had the chance) say they have a butter-smooth action and bench-rest accuracy.

Mauser followed up with the Model 77, a more conventional-looking bolt gun with three rear locking lugs and a detachable magazine, and then several commercial and military variations on the 66 and the 77. Then, in 1996, they brought out the M1996 straight-pull bolt gun, using a forward-mounted bolt handle at the front of the ejection port to operate its action. The M1996 was an awkward-looking thing and didn’t exactly take the market by storm.

But in Austria, another company also rebounded after the war.

Before World War II, the Mannlicher-Schoenauer rifles had a strong following all over the world. If one wishes to read of one used in an unorthodox fashion, read the Ernest Hemingway short story, "The Short, Happy Life of Francis Macomber."

The M-S rifle’s full-length stock became so iconic, in fact, that the design became known on all makes and models as a “Mannlicher stock.” The combination of the very first Mannlicher-Schoenauer rifle and its 6.5x54mm cartridge became something of a European equivalent of the Winchester 94 and the .30WCF round, an ideal combination of rifle and cartridge such that one can scarcely think of one without the other.

Following the war, Mannlicher re-established itself as a sporting gun manufacturer. Stoeger imported their rifles into the United States, said imports including the Models 1950, 1952, 1956, and 1961; but it was hard to top that original, the pre-war Mannlicher-Schoenauer.

Up in Finland, the Suojeluskuntain Ase- ja Konepaja Oy (Civil Guard Gun and Machining Works) or SAKO, spent the post-war years marketing the excellent Vixen (short action) and Finnbear (long action) bolt guns. Interestingly, and a bit off-topic, SAKO in 1961 introduced the only European-made lever gun I’m aware of, the full-stocked Finnwolf. In 1992, SAKO introduced the first of their renovated line with the 591 and finally, in 1997, they brought out the 75, followed in 2006 by the improved M85, which is still made today.

Across the Channel, the Brits were indulging in something they are very good at – producing works of art in walnut and blued steel. In olden times, the Brits had a great tradition of gun making, and two of their finest companies have a considerable history. But the first company we see across the Channel started in Ireland.

We can first cast ourselves back to 1775, when a chap named John Rigby went into business as a gunsmith in Dublin. I won’t go into all of Rigby’s history – that would take an article unto itself – but I will talk about their bolt guns. Rigby bolt guns were and are made on 98 Mauser actions, mostly big, beefy square bridge magnum actions, with walnut stocks you could fall in love with. Calibers are offered up to and including the .416 and .450 Rigby, so if you want to hunt Cape Buffalo or, maybe, a mid-size tyrannosaur, Rigby can set you up.

Over in London is a company bearing a name we must speak in an awed whisper: Holland & Holland. Founded by Harris Holland in 1835, Holland & Holland is the standard by which fine guns everywhere are measured. Their bolt guns, post-World War II, like Rigby, use a modified Mauser action, but each rifle is assembled and tuned by hand, by some of the best gunsmiths in the world. Calibers up to the .500 Nitro Express are available, and if you are willing to spend an amount of money that would otherwise buy you a pretty substantial house, you won’t find a more beautiful work of art in a rifle.

There are many more. In Serbia, the Zastava works turn out a pretty fair 98 Mauser action. These have been imported into the US in a variety of names, including the Herter’s J9 and the Interarms Mk X. I have one of the latter rifles, in .30-06, and it’s a solid rifle. Herter’s also imported a BSA bolt gun as the U9, and those rifles also enjoy a good reputation, as evidenced by how few are available on the various auction sites; people who have them are keeping them.

And Then This Happened

The modern era with its attention to all things tactical hasn’t excluded the bolt gun market. Indeed, some of the things that make a good tactical rifle also make a good hunting rifle, especially synthetic stocks, which may be ugly but are also tough and impervious to moisture and dirt. So, while the Tacticool craze encompassed bolt action rifles as well as other weapons, in the case of bolt guns that wasn’t all bad. We’ll examine that and other modern trends and the current state of the bolt gun world in general in the ultimate part of this series, coming up next.

One advantage the bolt-gun user has, as well, is that they are not - yet - the target for gun-grabbers, although it's important to note that the pro-gun movement has made some significant strides here in the United States recently.

See Related: Gun Control Advocates Have One Thing in Common: They Know Nothing About Guns

South Carolina Prepares to Join the Ranks of 'Constitutional Carry' States

I probably haven’t covered half of the notable bolt guns made for the sporting market in the 20th century. From the Great War onward, bolt guns have simply dominated the game fields the world over; they are cheaper and easier to make well than doubles, stronger and easier to adapt to heavy cartridges than lever guns, and acceptable in jurisdictions that disapprove of semi-autos. Doing justice to the history of the bolt gun and the state of the market today would require a book rather than a series of articles. If that’s what one was looking for, one could do a lot worse than to pick up a copy of Wayne Zwoll’s Bolt Action Rifles. Or maybe I’ll write a book on the topic myself.

I also have not covered .22 rimfire bolt guns at all. That may be an omission, but I can always do an article or two on rimfire rifles alone, and the more I think about it, that may be worth doing.

Meanwhile – stay tuned! We have one more segment in this history to go.